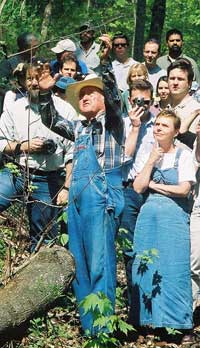

Kentucky authors mountaintop removal tour, April 2005

Testing new callout background color

Kentucky authors issue strong condemnation of mountaintop removal after tour and hearing

by Lucy Flood

On April 20, eighteen Kentucky authors set off on a mountaintop removal tour coordinated by KFTC. By the end of their two-day expedition, many said they were permanently changed by seeing the devastating legacy of coal mining in eastern Kentucky and hearing the stories of coalfield residents trying to survive this assault.

In a statement written and released by the authors at the conclusion of their tour, they strongly condemned mountaintop removal in the following words:

“We are horrified that this practice is legal. We are angry that representatives in our own government are allowing this to happen. Mountaintop removal is not right; it is not acceptable, and it is an act we will fight.” See full statement …

Daymon Morgan, a KFTC member whose family has lived for generations along Lower Bad Creek in Leslie County, led the first part of the expedition. Dressed in a straw hat and shiny black cowboy boots, Morgan climbed into his six-wheeled ATV and guided the group along a zigzagging route through the healthy forest above his house.

Stopping in a shaded area beneath the tree canopy, Morgan bent over and ran his fingers through the dark soil of the forest floor. As he lifted it up, letting the dirt sift through his fingers to the ground below, he explained that it takes thousands of years for the forest’s organic material to biodegrade into such rich earth.

By contrast, mining can permanently disrupt the soil composition of entire mountains in a matter of minutes.

“It’s very disturbing for me to see the things I love being destroyed,” Morgan said.

Just as eloquent as his words was the way in which he moved through the forest, pointing out medicinal plants. His impromptu lesson on the uses of wild plants informed the authors about the importance of protecting biologically diverse forests.

From there, the group moved up to the ridge of Morgan’s land and watched as a bulldozer tore away at the base of the mountain, leaving behind a mass of discarded trees and wasted earth.

In reward for marching up and down the hillside, the authors were served a feast by the Morgan family.

After eating lunch on the porch of the Morgan’s log house, the group continued to the Hazard airport, stopping along the way to observe what remains after a mountain top has been removed.

The group saw miles of flattened mountains, a desert plateau reaching to the horizon. Although some areas had been hydro-seeded and planted in non-native olive trees, one of the few species that can grow in such poor soil, the mountains were generally barren of life.

Later in the trip the authors heard from Larry Easterling about the condition the coal companies leave the land. Easterling, said that although the coal companies are supposed to return the mined land to a “higher and better” use, “there is nothing higher and better. All you get is some grass that turns brown in the winter, and thorns.”

As the authors walked along the reclaimed ridge where Morgan grew up and affectionately referred to as “Huckleberry Ridge,” he reminisced about his childhood home.

“I was raised right over here on the fork. I used to hunt back in here. We tended the corn in here, too,” Morgan recalled. “We didn’t have any fertilizer, but we didn’t need any. Now that apple orchard is all tore up. The beech trees are gone. At one time this was rich land, but now all that grows is scrub.”

Stopping at a bend in the road, Morgan pointed into the olive trees. There sat a boulder that had been launched from a nearby mountain in one of the explosions used to level the mountains.

“You’d never believe there was anything powerful enough to blow those mountains all the way over here,” Morgan said.

Not surprising, the explosions that flung the boulder all the way to Huckleberry Ridge also buried the stream where Morgan fished as a boy. None of the long list of bird species he once saw continues to inhabit the area.

Some authors questioned whether any amount of fertilizer would ever be able to get anything but olive trees and African grasses to grow there again.

At the Hazard airport, the group viewed mountaintop removal from the air. Ed Mc-Clanahan, author of The Natural Man, compared what he saw to a moonscape. The authors witnessed mountains leveled into short plateaus, sludge ponds, reclaimed areas and mountains erupting upwards in dirt volcanoes.

While the authors took turns going up in the planes, Eastern Kentucky University professor Dr. Alice Jones, described the impacts of mountaintop removal on Kentucky waterways. Research she presented made it clear that all Kentuckians pay for the devastation in eastern Kentucky by having water downstream polluted.

Sediment is the number one pollutant in the Kentucky River, Jones reported, more than 50 percent of which comes from mining. This pollution affects the water supply of 720,000 households who live in communities downstream on the Kentucky River. It is these individuals and communities, not coal companies, that pay to have mining silt filtered from their water.

Even more moving than the aerial views were the testimonies the authors heard at the Hindman Settlement School that evening. In the crowded room person after person spoke. For a full two hours, the authors, renowned for their ability to work words into compelling stories, sat speechless.

Randy Wilson, the moderator, began by singing a song that carried the theme of yearning for just “a little spring of water.” His song was particularly relevant given the fact that Erica Urias, the first person to address the authors, stated that she was afraid to bathe her daughter for fear that the polluted water in the tub might get into her mouth.

When Urias commented that, “We are human beings and we have rights and dreams,” she revealed how many people in the region are made to feel by the coal companies — a sense of being less than human.

Another woman was infuriated because mining caused a section of her road to erode, preventing ambulances and school buses from getting through.

John Roark, a Perry County resident, echoed her frustration with road conditions, “The companies don’t pay to keep up one inch of these roads. They’re getting filthy rich and don’t put a dime back into the community,” he said.

The authors also learned of a one-mile section of road where four families grieve for their children, killed by overloaded coal trucks involved in fatal traffic accidents.

Identifying a lack of effective laws and enforcement as a major problem, Letcher County Judge-Executive Carroll Smith said, “There’s the case of a house that had one foot of mud in it, yet the inspector defended the coal company. Why? Because he couldn’t find any anything to write the coal companies a citation for. Neither the state or the federal government will find fault with a coal company for sinking a house. Any law that allows a company to flood a person’s home is wrong.”

Summarizing the opinions of many of the people in the room, Roark said, “The low cost of energy is not low cost if you live in eastern Kentucky. It’s high cost.”

The following morning in a story about the tour, the Lexington Herald Leader quoted Bill Caylor, president of the Kentucky Coal Association, as saying, “We’re creating land for sustainable development for future generations.”

Outraged at what they’d heard and seen, and further infuriated by Caylor’s statement, the authors convened to write a manifesto calling for the abolition of mountaintop removal. They produced a strongly worded document that everyone enthusiastically endorsed.

Later in the day they took their first public action when they presented their manifesto and individual reflections on the trip at a press conference at Eastern Kentucky University.

Since then, the authors have written several op-eds against mountaintop removal and spoken out against it. They plan to meet again in May and to continue learning about the issue and to take action to prohibit such destructive mining practices.

The authors hope their voices may allow the stories of eastern Kentuckians to reach the desks of legislators who have the power to ensure that the lives and landscapes of eastern Kentucky do not continue to be ravaged by mountaintop removal.

- Home

- |

- Sitemap

- |

- Get Involved

- |

- Privacy Policy

- |

- Press

- |

- About

- |

- Bill Tracker

- |

- Contact

- |

- Links

- |

- RSS