Ohio River pollution control agency wants to abandon its water quality standards

“Protect our water” was the strong and clear message of close to 100 people who attended a July 26 public forum on a proposal to abandon regional water standards for the Ohio River by the multistate Ohio River Valley Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO).

“Only a few years after the water crisis of Flint and Standing Rock, we are on the verge of another nightmare in which regulators are more interested in carrying out the wish list of polluting industry than protecting the health of the public.” said Eira Tansey, a member of Metro Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Democratic Socialists of America.

ORSANCO was established on 1948 as a compact between eight states and the federal government to control and abate pollution in the Ohio River basin. But now the commission is proposing an industry-backed plan to do away with its standards, letting states set pollution standards.

Yet all who spoke pointed out that often the commission’s standards well surpass those set by the federal Clean Water Act and state laws. And despite stronger regional standards, the Ohio River remains the most polluted inland waterway in the country.

The river hosts 26 coal-burning plants along its banks, about one every 38 miles. Five million people from eight states rely on drinking water from the river.

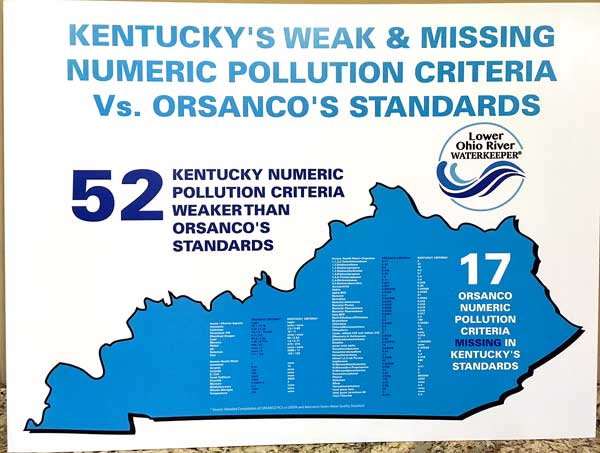

At least 100 pollutants for which there are no federal or state standards are included in ORSANCO’s standards. Fifty-two of Kentucky’s water quality standards are weaker than ORSANCO’s.

Gutting regional standards would leave an uneven network of weaker individual state regulations, many commenters pointed out. And the proposal comes at a time when the federal Environmental Protection Agency is being undermined in Washington, DC.

Public comment was passionate and opposed

I attended the public hearing with other members of the Northern Kentucky KFTC Chapter, as well as individuals who call the river area their home and members of a wide swath of environmental and activist organizations.

We heard well-researched arguments by public health and environmental scientists and activists who have been long involved in the fight to protect our water.

We heard well-researched arguments by public health and environmental scientists and activists who have been long involved in the fight to protect our water.

Epidemiologist Colleen Kaelin of Frankfort recently retired from the Kentucky Department of Public Health where she served as the epidemiologist in charge of environmental health impacts.

“My main focus has been the impact of climate change on public health,” she said. “One of the things we’ve seen is that virtually every major waterborne disease outbreak has been preceded by and extreme precipitation event. The forecast for the coming years is more frequent and more extreme weather events of all kinds including heavy rainfall.”

This is not the time to be deregulating, she said. “We need to increase the watchfulness over our water quality because we will be seeing more infectious disease outbreaks, more situations similar to the lead poisoning in Flint if we do not continue to consistently monitor our water quality and our water security.”

Indra Frank, a physician and director of environmental health and water policy at the Indiana-based Hoosier Environmental Council, addressed the claim of redundancy. She took information about her state directly from a report by ORSANCO comparing its standards to those of member states and the EPA.

“There are 54 ORSANCO standards that Indiana does not have at all and 63 ORSANCO standards that are more protective than the Indiana standards. So, there are more than 100 standards that are not redundant along the Indiana stretch of the river,” she pointed out.

Frank also noted that Indiana state administrative code references ORSANCO standards and would have to be rewritten at great expense if the state wanted to reestablish the standards lost if ORSANCO abandons them.

Dangerous connections

We also heard from activists and community organizers who were angered by the influence of corporate money on the commissioners and their decisions. Three commissioners are appointed by each of the governors of the eight states along the river, and three are appointed by the federal government.

Eira Tansey questioned where commissioners’ interests lie.

“We’ve been told that the majority of commissioners favor … a path towards deregulation that happens to line up with the interests and stated preferences of polluting industry.”

Ohio’s status as one of the dirtiest rivers in the country can be directly traced to companies that have requested the commission relax its standards, she added, including Alcoa, AK Steel, American Electric Power, ArcelorMittal, First Energy, Duke Energy and Jupiter, who all have had dozens of Clean Water Act violations in recent years.

“Half of the commissioners have ties to polluting industry. They have either worked directly in the mining and energy industries or they’ve represented them as clients of their consulting firms and law practices.”

Among those with industry ties, Tansey listed Commissioner [Charles] Snavely of Kentucky, who retired from Excel Mining, and West Virginia commissioners Austin Caperton, who worked at Massey Energy; David Flannery, who serves on the National Coal Council; and Ronald Potesta, chair of the commission, who has represented clients such as Dupont, one of the worst polluters of the river.

“This is not sound science or policy making,” she concluded. “This is the fox guarding the hen house door. If the commission guts regional pollution control standards, it is selling out the health and safety of everyone living downstream from polluting industry for the ability of corporations to make more money.”

Individuals voice fears and concerns

The most moving comments came from those who live in the small river towns of Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky, whose families have relied on the river for decades. Army veteran Melanie Phillips participates in a recreation program for veterans and said the river is one of the only places she finds peace to deal with PTSD and other issues.

Another person said she remembered a childhood playing in a creek that feeds into the river and questioned whether her grandchildren will never know that joy.

The meeting drew people young and old. Students from the Kentucky Student Environmental Coalition were well represented.

“Things like this are extremely upsetting. I can’t help getting angry,” KSEC member Emma Anderson said. “I grew up on the Ohio River, swam in the river every day in the summer. It’s a part of me, I miss it like a friend when I’m gone. It’s just a bad idea.”

Noland Aull also is a member of KSEC and an environmental commissioner for Fayette County.

“There’s this abdication from the top down of responsibilities. There’s this very toxic concept that leaving it up to the free market will create a push for moral behavior, this good stewardship. It’s been proven time and again to just not be the case,” Aull said. “It never works out, much to the chagrin of local populations who have to deal with the aftermath and who are the least prepared to do so. The abdication of authority, the abdication of responsibility is definitely something to be concerned about.”

To sum up, people are angry and concerned about what might happen if the more stringent ORSANCO standards should go away. They do not buy the argument that its standards are redundant and are concerned that this move could increase pollution and negatively impact the vital Ohio River water for decades to come.

To weigh in on the issue, the email is [email protected] to submit comments. The address is ORSANCO, 5735 Kellogg Ave., Cincinnati OH 45230. The deadline to submit comments is August 20.

To read more information about the PCS program or this comment period, the website is: www.orsanco.org/programs/pollution-control-standards/

Recent News

Kentucky’s past legislative session showed alarming trend toward government secrecy

Churchill Downs takes more than it gives. That's why the Kentucky Derby is a no-go for me

‘We must never forget.’ Kentucky town installs markers for lynching victims.

Featured Posts

Protecting the Earth

TJC Rolling Out The Vote Tour – a KFTC Reflection Essay

KFTC Voter Empowerment Contractor Reflection Essay

Archives

- Home

- |

- Sitemap

- |

- Get Involved

- |

- Privacy Policy

- |

- Press

- |

- About

- |

- Bill Tracker

- |

- Contact

- |

- Links

- |

- RSS