Indigenous Lands Acknowledgment

Acknowledging our presence on indigenous land

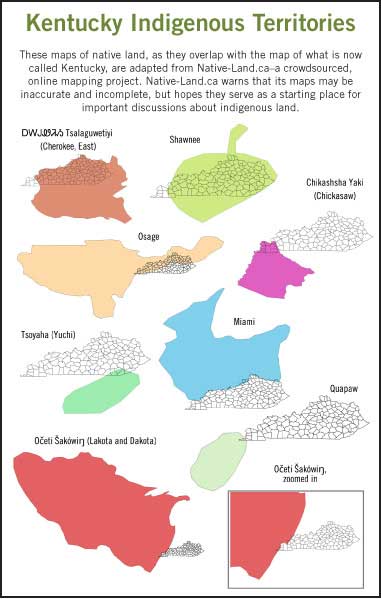

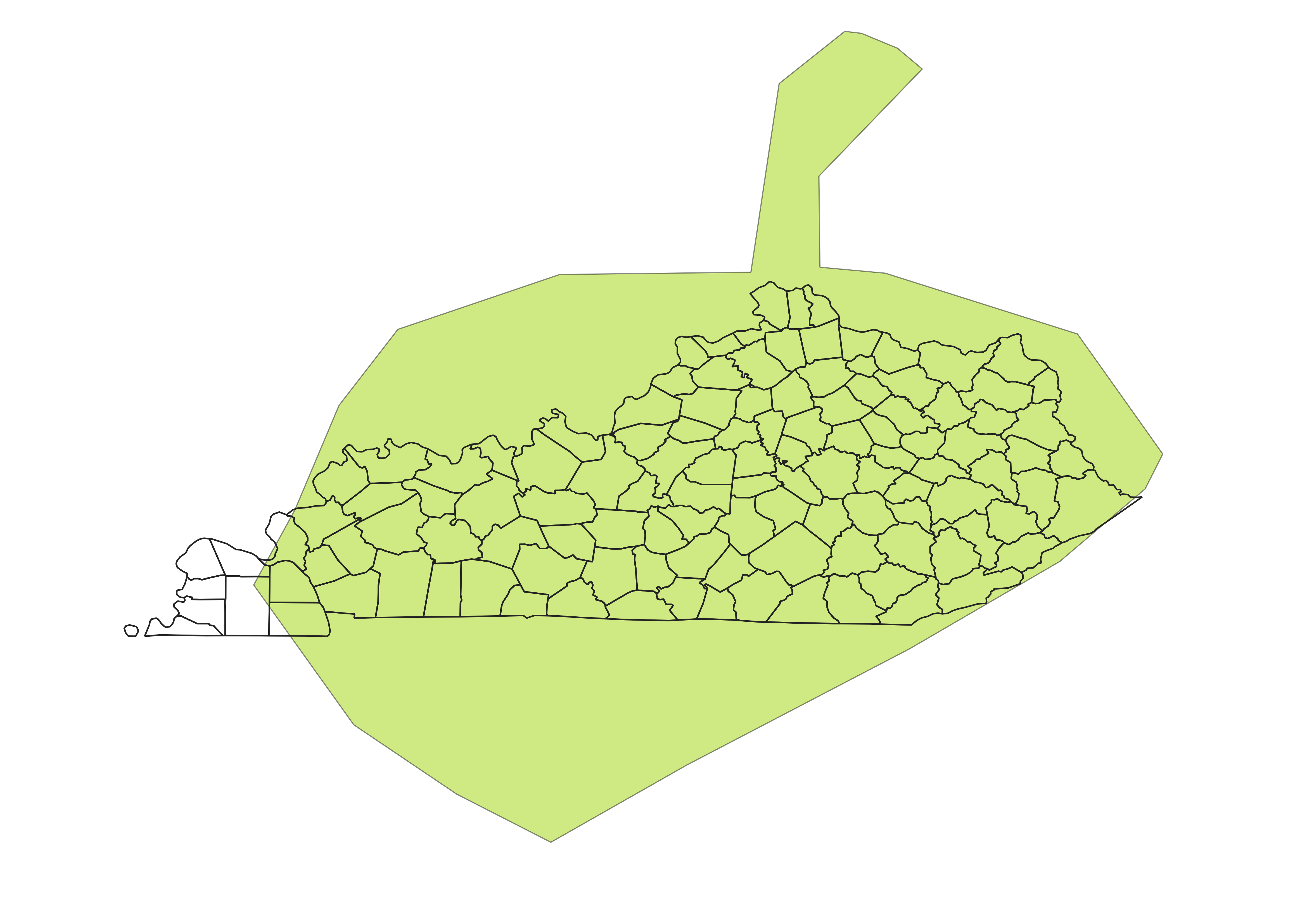

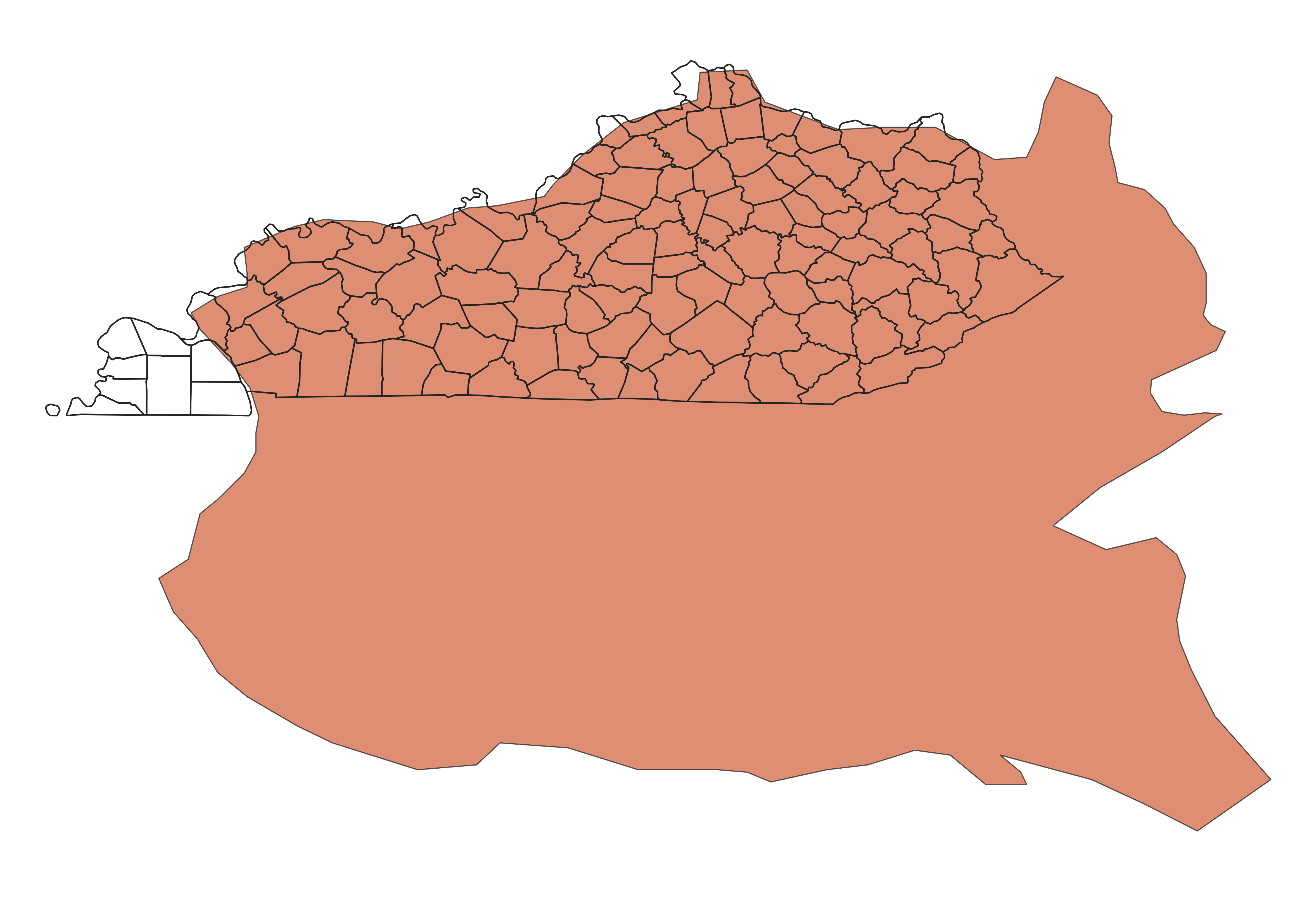

At the annual meeting, members received written information (a portion follows) and a brief presentation about the indigenous people who called Kentucky home before the land was taken from them.

Compiled by Big Sandy chapter members with help from Madison County member Wendy Warren and staff member Nikita Perumal

Indigenous peoples have always lived on the land that is now called Kentucky, and continue to live here today. The place we now call Kentucky is primarily Shawnee, Cherokee, Chickasaw and Osage land.

A commonly cited claim many of us heard in history class growing up is that this region was merely a hunting ground. This claim is a myth, perpetuated at first by land speculators who wished to improve land sales, and still today as a way to absolve settler colonists and their descendents from grappling with their history of land theft, genocide, and white supremacy. The continuation of this myth is harmful for all of us.

Indigenous peoples have lived on the land now called Kentucky for at least 12,000 years. Over thousands of years, various indigenous nations and cultures have called this place home–many with overlapping histories and territories. Those that avoided/survived forced relocation still have a large presence here, but not an effortless one. The Trail of Tears is only one piece of a very painful history for Natives on the land that would become Kentucky; assimilation and suppression are common experiences that were necessary for survival. For many Native peoples in Kentucky, this meant traditions kept quietly, languages passed on a few words at a time, hidden preservation of connections.

They are still here. In the 2010 Census, there were a recorded 31,335 Native Americans living in Kentucky.

Berea College sits on Shawnee and Eastern Band Cherokee land.

It’s important to note that native history and culture can not be easily summarized, and it is our responsibility to learn carefully and respectfully. You can refer to the supplemental materials provided in your folder to learn more about the Shawnee and Cherokee. We also encourage you to research their practices, history, and way of life. When possible, it is best to refer mostly to the tribes themselves for their historical accounts, as erasure in academia is a significant problem.

It’s important to note that native history and culture can not be easily summarized, and it is our responsibility to learn carefully and respectfully. You can refer to the supplemental materials provided in your folder to learn more about the Shawnee and Cherokee. We also encourage you to research their practices, history, and way of life. When possible, it is best to refer mostly to the tribes themselves for their historical accounts, as erasure in academia is a significant problem.

Native people are still here, and are fighting for a wide variety of issues that are critically important to recognize:

In the United States, there is an epidemic of murdered and missing indigenous women. Today, four out of five native women are victims of violence–and that is only what gets reported. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, American Indian women face murder rates more than 10 times the national average. In the United States in 2016, 5,712 murdered and missing indigenous women were reported, but only 116 were logged in the Department of Justice missing persons database. Homicide is the 3rd leading cause of death among native girls and women ages 10-24. It is the 5th leading cause of death among native women ages 25-34.

“Indian” sports mascots are harmful, perpetuate negative stereotypes and contribute to a disregard for the personhood of Native peoples. For Native children in Kentucky whose schools have “Indian” mascots, these practices create a shameful image of their identity and leaves the children to hide who they are. These mascots can contribute to bullying and harassment of Native children, and crafts a racist narrative of Native peoples as less than human.

Many Native peoples are at the forefront of the fight for environmental justice and protection. In Kentucky, honoring these struggles can look like many things – from protecting water quality in the Ohio River, to resisting extraction sites like the failed Kinder Morgan pipeline, to centering indigenous stewardship, resistance, and knowledge (and combating erasure) in our organizing efforts for a just transition.

Potential Action

Host reading groups and discussions that build an understanding of settler colonialism and your community’s relationship to it that is tied to indigenous solidarity. Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz’s “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States” is a potential place to start.

If you are part of a Christian denomination that has not yet repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery – the theological justification for the theft of indigenous land – start or join a movement to do so.

Support education and resource sharing for collective action towards land repatriation to Indigenous people in the ongoing struggle against colonization. Consider learning more about decolonization and land reparations, at the Resource Generation guide on solidarity through land reparations (https://resourcegeneration.org/land-reparations-indigenous-solidarity-action-guide)

Native-led organizations to support

- Proud to Be

- The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women

- Greater Cincinnati Native American Coalition

- IllumiNative

- Change the Mascot

Sources

- Official websites of the Shawnee and Eastern Band Cherokee

- LexHistory.org

- Kentucky Heritage Council

- “Dispelling the Myth: Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Indian Life in Kentucky” by A. Gwynn Henderson

- Native-Land.ca

Additional Information

The land we are occupying belongs to the Shawnee and Eastern Band Cherokee peoples. This additional information is oversimplified and incomplete but can be a starting place to educate ourselves about Kentucky’s shared history of white supremacy and settler colonialism, and about ways to act in solidarity with the original inhabitants of this land.

Shawnee

The Shawnee people primarily organized themselves around village bands as ritual and economic units. They had a corn based agricultural society, and farmed in villages during the summer. In the winter, they would travel to hunt and make maple sugar. They also made salt, and traded with Europeans after colonization began.

The Shawnee had a governing council, which made decisions by consensus and had a greater decision-making power than wartime or peacetime chiefs. Legal issues and criminal disputes were mostly decided privately, or occasionally by the governing council. Children were educated by their grandparents, and women could serve as chiefs.

The Shawnee had a governing council, which made decisions by consensus and had a greater decision-making power than wartime or peacetime chiefs. Legal issues and criminal disputes were mostly decided privately, or occasionally by the governing council. Children were educated by their grandparents, and women could serve as chiefs.

Shawnee religious practices and rituals revolved around crops and harvests, hunts, and the warding off of disease. Shawnee medicinal skills were well reknown. Nearly everyone in the tribe was familiar with how to use medicinal roots and herbs, and their doctors were sought out by both white colonialists and other tribes.

One of the most well-known Shawnee leaders was Chief Tecumseh, a natural and charismatic leader whose speeches are widely recognized for their power and impact.

The Shawnee’s way of life was disrupted by encroaching white settlers, and they were often forced to leave their lands in search of unoccupied territory out west. Shawnee warriors fought in land skirmishes, particularly with the Kentucky militia, who destroyed their villages and crops. They were systematically pushed westward via violence and racist legislation such as the Indian Removal Act.

The Shawnee Tribe became a federally recognized Tribe when Congress enacted the legislation known as Public Law 106-568, or the Shawnee Tribe Status Act of 2000. Their tribal headquarters are now in Oklahoma.

“And I want to know your intentions. I want to know what you are going to do about taking our land. I want to hear you say that you understand now, and you will wipe out that pretended treaty, so that the tribes can be at peace with each other, as you pretend you want them to be. Tell me, Brother. I want to know.”

-Chief Tecumseh

Eastern Band Cherokee

Eastern Band Cherokee peoples organized themselves predominantly via matrilineal clans, and they lived in villages with 30 - 60 households. Clans would decide the village chiefs. All Cherokee towns were built with a council house, used for political and ceremonial purposes, in which burned a sacred fire. Towns also had a peace and war chief, with councils for each. Children were educated not by their fathers, who were of a different clans, but by their mother’s brother.

Former to forced removal, the Cherokee practiced six main religious festivals throughout the year. They held sacred many entities, including the numbers four and seven, circles, water, and cardinal directions. Also important to Cherokee culture were the notion of spiritual beings, and Medicine People–highly trained individuals who oversaw Cherokee religion and medicine.

Former to forced removal, the Cherokee practiced six main religious festivals throughout the year. They held sacred many entities, including the numbers four and seven, circles, water, and cardinal directions. Also important to Cherokee culture were the notion of spiritual beings, and Medicine People–highly trained individuals who oversaw Cherokee religion and medicine.

The Cherokee developed a written constitution in the early 1800s. In 1821, a Cherokee scholar named Sequoyah completed a written Cherokee language and just 7 years later, a Cherokee language newspaper began publishing. Cherokee literacy rate quickly surpassed that of surrounding European settlers.

In 1838, greed for more land and Georgia gold gave the government an excuse to forcefully remove Cherokee in the Southeast. More than 16,000 Native people were marched on what would historically become known as the Trail of Tears and relocated to Oklahoma. Between 25% and 50% of the Cherokee tribe died on the Trail of Tears.

Today, many of the sovereign Eastern Band Cherokee nation live on 57,000 acres of land called the Qualla Boundary, near the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Chief Yonaguska, a Cherokee leader who deeply resisted relocation, worked to provide a home for the Eastern Band by having his adopted (white) son make the Qualla boundary land purchase in a time when it was illegal for Natives to purchase lands.

Decolonization and Reconciliation

*Adapted from: “Pulling Together: A guide for Indigenization of post-secondary institutions. A professional learning series.”

For people of settler identity, the legacy of settler colonialism in this country is deeply engrained in our mindsets, practices, institutions, stories, and in our organizing spaces. Decolonization refers to the process of deconstructing the colonial ideologies embedded in our thinking–particularly those that imply the superiority and privilege of Western thought and approaches. It involves:

-

dismantling structures that perpetuate the status quo

-

problematizing dominant discourses

-

addressing unbalanced power dynamics

-

valuing and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge and approaches

-

weeding out settler biases or assumptions that have impacted Indigenous ways of being

-

Following Indigenous leadership, building relationships, and learning how best to show up in solidarity with indigenous struggles

For individuals of settler identity, decolonization is the process of examining your beliefs about Indigenous Peoples and culture by learning about yourself in relationship to the communities where you live and the people with whom you interact. At the same time, decolonization efforts should be done in accordance with leadership by indigenous peoples. Decolonization for indigenous peoples is inherently different by nature.

Those engrossed in decolonization also often speak of reconciliation–an ongoing process of addressing past wrongs done to Indigenous Peoples, making amends, and improving relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to create a better future for all. The responsibility for reconciliation must primarily fall on the settler society–not on Indigenous peoples. Settlers must work to gain in-depth understanding of our relationship to Indigenous Peoples and the impacts of colonization, including recognizing settler privilege and challenging the dominance of Western views and narratives.

The processes of decolonization and reconciliation for Kentuckians with settler identities will require intentionality, patience, and accountability. Here are some places to begin:

-

Read and complete the attached Indigenous Resistance Homework worksheet to begin the process of thinking about our role in colonization and decolonization

-

Read the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and support efforts for the United States to adopt it, and for our educational institutions to teach it

-

Host reading groups and discussions that build an understanding of settler colonialism and your community’s relationship to it that is tied to indigenous solidarity. The resources on the next page are a great place to start

-

Build relationships and learn about best practices for being in solidarity with indigenous-led movements. Look to the article “How to support Standing Rock and confront what it means to live on stolen land” for specific guidance.

-

Support resource sharing and collective action for land repatriation to Indigenous people in the ongoing struggle against colonization.

-

If you are part of a Christian denomination that has not yet repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery –the theological justification for the theft of indigenous land–start or join a movement to do so.

Resources Available Online

Indigenous Resistance Homework: Questions about “Home” - Catalyst Project

Reclaiming Native Truth: A Project to Dispel America’s Myths and Misconceptions

“Pulling Together: A guide for Indigenization of post-secondary institutions. A professional learning series.” by Asma-na-hi Antoine, Rachel Mason, Roberta Mason, Sophia Palahicky, and Carmen Rodriguez de France

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

“How to support Standing Rock and confront what it means to live on stolen land” - Waging Non-Violence.org

Resource Generation guide on solidarity through land reparations - Resource Generation website

Kitchen Table Dialogue Guide - Reconciliation Canada

“Decolonizing Our Practice - Indigenizing Our Teaching” by Shauneen Pete, Bettina Schneider, and Kathleen O’Reilly

Kentucky Heritage Council - Teaching About Native Americans

“A Native Presence” television series, available on Kentucky Educational Television’s website

“Dispelling the Myth: Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Indian Life in Kentucky” by A. Gwynn Henderson

“Remembering Slack Farm” by A. Gwynn Anderson

“Students lead push to teach African, Native American history in Kentucky classrooms” - Lexington Herald Leader

- Home

- |

- Sitemap

- |

- Get Involved

- |

- Privacy Policy

- |

- Press

- |

- About

- |

- Bill Tracker

- |

- Contact

- |

- Links

- |

- RSS