How does mountaintop removal affect our water?

Conductivity

In April 2010, based on scientific research, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced an in-stream limit for conductivity at 500 microsiemens (µS). It is at that level and above, research showed, that aquatic life disppears.

This standard is vehemently opposed by the coal industry and the Beshear administration. Why? Because many streams are so severely polluted from past mining that conductivity levels already exceed 500 µS. Water testing by KFTC members show levels exceeding 1,200 µS to be common, with levels as high as 4,700 µS recorded.

"Conductivity gives us the first sign that something may be wrong with our water. It is a great tool for people in Appalachia. It may not tell you what exactly is wrong but it does tell you something is wrong and further testing is needed.

"Conductivity gives us the first sign that something may be wrong with our water. It is a great tool for people in Appalachia. It may not tell you what exactly is wrong but it does tell you something is wrong and further testing is needed.

"I’ve tested a creek where the water was crystal clear but the conductivity meter ran over 4000 µS. That told me something was wrong, and after further testing was done we saw how bad it was – some of the pollutant levels were 100 times the safe water standard."

Rick Handshoe

Floyd County

In Appalachia, water is more than the sustenance of life. Our streams help define our understanding of place, of where we come from. Clean water is needed for healthy people and healthy communities, and for the future we want to build for our region.

So we must react strongly and quickly when our water is damaged or threatened, which in eastern Kentucky is, unfortuately, widespread and severe from mountaintop removal and other forms of mining. This includes surface water, ground water and even municipal water supplies that use for their source waterways polluted by coal companies.

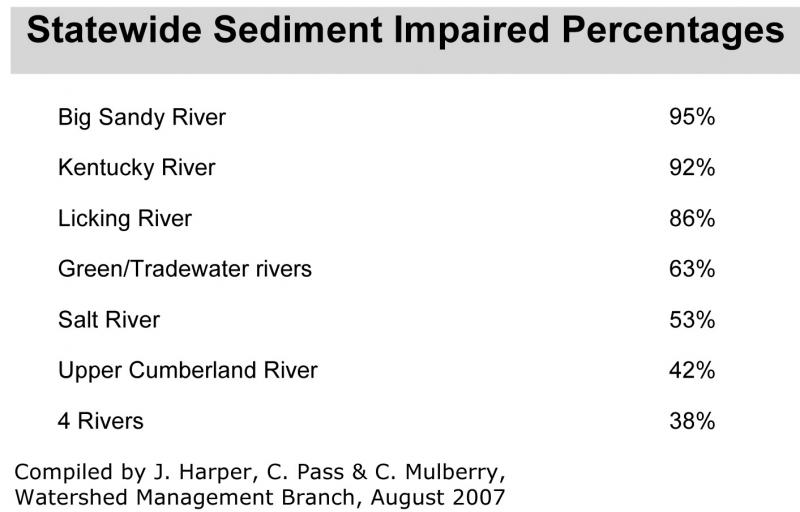

Most of this pollution, according to the state report, comes from "resource extraction," which is primarily strip mining but also includes logging and land disturbance from oil and gas drilling.

The primary pollutant is sedimentation, which carries with it a variety of toxic metals and salts, including selenium. Acid mine drainage also is a result of the leaching of chemicals from the rock that is exposed by mining practices.

Under the Clean Water Act, states are required to develop a list (called the 303 (d) list) of all polluted streams and what are those pollutants. When a stream is on this list, the state is required to place measurable limits on any new and existing sources of pollution go give the stream a chance recover. These are called Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) limits on pollution.

But while sedmentation from "resource extraction" is the primary pollutant in eastern Kentucky streams, state water officials have never created TMDL limits for sedimentation. As a result, in the Big Sandy River basin data from the Kentucky Division of Water shows that 95% of streams remain "impaired" – that is, not able to support their designated use(s).

Another way that coal companies get around pollution limits is by being covered by the 402 KPDES (Kentucky Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) general permit.

Protecting our water is at the center of organizing efforts of KFTC members across the region to stop the mining that threatens our communities, including in Benham and Lynch, Wilson Creek, Hueysville, and elsewhere. We're part of several lawsuits to mandate enforcement of the Clean Water Act. We've brought the governor, members of Congress and top officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to eastern Kentucky to see firsthand the damage to our water. And we're putting science in the hands of community residents through the Community Science and Public Health project.

Data

The impacts of mining on water quality are well-documented. Here are some resources:

- Mountaintop Mining Consequences by Dr. Margaret Palmer and others

- Home

- |

- Sitemap

- |

- Get Involved

- |

- Privacy Policy

- |

- Press

- |

- About

- |

- Bill Tracker

- |

- Contact

- |

- Links

- |

- RSS